[ad_1]

Art Garfunkel once described his legendary musical chemistry with Paul Simon: “We meet somewhere in the air through the vocal cords …” But a new study on the songbird duet from Ecuador has offered another melody that explains the mysterious connection between successful duos.

It is a bond of their minds, and it happens, in fact, when each singer silences the brain of the other while coordinating their duets.

In one study, a team of researchers studying the brain activity of singing male and female flat-tailed wrenches has found that the species synchronizes their frenetic-paced duets, surprisingly, by inhibiting regions of their partner’s brain that make songs while they exchange phrases.

The researchers say that the auditory feedback exchanged between the kings during their opera duets momentarily inhibits the motor circuits used for singing in the listening partner, helping to link the brains of the pair and coordinate taking turns for a seemingly performance. telepathic. The study also offers new insight into how humans and other cooperative animals use sensory cues to act in concert with each other.

“You could say timing is everything,” said Eric Fortune, a co-author of the study and a neurobiologist in the Department of Biological Sciences at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.

“What these kings have shown us is that for good collaboration, partners must become ‘one’ through sensory bonding. The take-home message is that when we cooperate well … we become a single entity with our partners. “

“Think of these birds as jazz singers,” added Melissa Coleman, corresponding author of the article and associate professor of biology at Scripps College. “Duet wrenches have a rough song structure planned before singing, but as the song evolves, they must coordinate quickly by receiving constant feedback from their counterpart.

“What we were hoping to find was a highly active set of specialized neurons coordinating this turn-taking, but instead what we found is that listening to each other actually causes the inhibition of those neurons, that’s the key that regulates the incredible synchronization between the two. “

MORE: Falcons Have Natural ‘Eye Makeup’ To Improve Hunting Ability, Scientists Find

For the study, the team had to travel to the heart of the flat-tailed wren’s music scene, within the remote bamboo forests on the slopes of Ecuador’s active Antisana volcano.

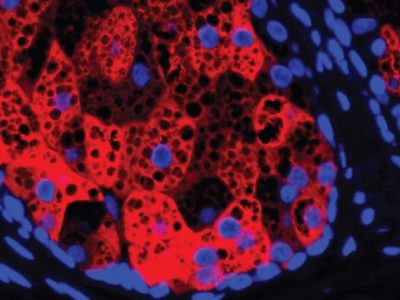

Camped out in the laboratory of the Yanayacu Biological Station, the team made neurophysiological recordings of four pairs of native kings while they sang solo and duet songs, analyzing sensorimotor activity in a premotor area of the bird’s brain where specialized neurons are active for learning and make music.

The recordings showed that during duet taking, which often takes the form of call-and-answer phrases, or syllables, which together sound as if a single bird were singing, the birds’ neurons were firing rapidly as they produced their own syllables.

However, when a wren begins to hear its partner’s syllables sung in duet, neurons slow down significantly.

“You can think of inhibition as acting as a stepping stone,” Fortune explained. “When birds listen to their mate, the neurons are inhibited, but just like when they bounce off a trampoline, the release of that inhibition causes them to respond quickly when it is time to sing.”

The team then played back recordings of wrenches doing duets while in a sleep-like state, anesthetized with a drug that affects an important inhibitory neurotransmitter in the wren’s brains also found in humans, gamma acid. -aminobutyric (GABA). The drug transformed activity in the brain, from inhibition to bursts of activity when the kings listened to their own music.

“These mechanisms are shared or similar to what happens in our brain because we are doing the same kinds of things,” said Fortune, whose study has been published in procedures of the National Academy of Sciences. “There are similar brain circuits in humans that are involved in learning and coordinating vocalizations.”

Fortune and Coleman say the results offer a new look at how the brains of cooperating humans and other animals use sensory cues to perform in concert with each other, starting with flowing musical and dance performances, or even the disjointed sensation of inhibition that is commonly experienced today during video. conferences.

(CLOCK the video illustrating this research below).

[ad_2]

Original