[ad_1]

An international research team has retraced the amazing journey of the life of an arctic woolly mammoth, which covered enough of the Alaskan landscape during its 28 years to nearly circle the Earth twice.

Scientists collected unprecedented details of his life through analysis of a 17,000-year-old fossil from the University of Alaska Museum of the North. By generating and studying isotopic data on the mammoth’s tusk, they were able to match its movements and diet with isotopic maps of the region.

Few details have been known about the life and movements of woolly mammoths, and the study offers the first evidence that they traveled great distances. A summary of mammoth life is detailed in the new issue of the journal Science.

“It’s unclear if it was a seasonal migrant, but it covered some serious ground,” said University of Alaska Fairbanks researcher Matthew Wooller, lead author and co-lead author of the paper. “He visited many parts of Alaska at some point in his life, which is quite surprising when you think about how big that area is.”

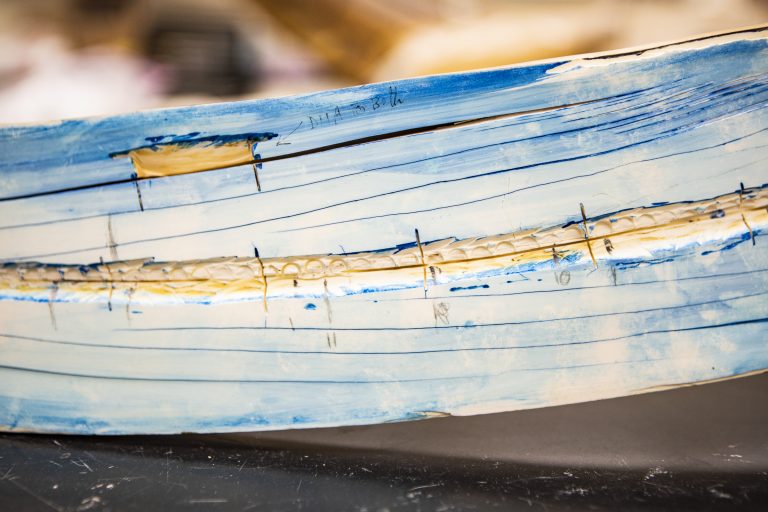

Researchers at the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility, where Wooller is director, split the 6-foot tusk lengthwise and generated about 400,000 microscopic data points using a laser and other techniques.

The detailed isotope analyzes they did are possible due to the way the mammoth tusks grew. Mammoths constantly added new layers every day throughout their lives. When the tusk was split lengthwise to sample, these growth bands looked like stacked ice cream cones, providing a chronological record of the life of an entire mammoth.

“From the moment they are born to the day they die, they have a journal and it is written on their fangs,” said Pat Druckenmiller, paleontologist and director of the UA Museum of the North. in a sentence. “Mother Nature does not often provide such convenient and long-lasting records of an individual’s life.”

Scientists knew that the mammoth died on the northern slopes of Alaska above the Arctic Circle, where its remains were excavated by a team including Dan Mann and Pam Groves of the UAF, who are among the study’s co-authors.

The researchers reconstructed the mammoth’s journey to that point by analyzing isotopic signatures in its tusk from the elements strontium and oxygen, which were combined with maps that predicted isotope variations in Alaska. The researchers created the maps by analyzing the teeth of hundreds of small rodents from across Alaska found in the museum’s collections. Animals travel relatively small distances during their lives and represent local isotopic signals.

Using that local data set, they mapped isotope variation in Alaska, providing a baseline for tracking mammoth movements. After accounting for geographic barriers and the average distance traveled each week, the researchers used a novel spatial modeling approach to map out the likely routes the animal took during its lifetime.

The ancient DNA preserved in the remains of the mammoth allowed the team to identify it as a male that was related to the last group of its species that lived in mainland Alaska. Those details provided more information about the animal’s life and behavior, said Beth Shapiro, who led the DNA component of the study.

For example, an abrupt change in its isotopic signature, ecology, and movement around age 15 likely coincided with the expulsion of the mammoth from its herd, reflecting a pattern seen in some male elephants today.

“Knowing that he was male provided a better biological context in which we could interpret the isotopic data,” said Shapiro, a professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

The isotopes also offered a clue as to what led to the animal’s demise. Nitrogen isotopes increased during the last winter of its life, a sign that may be a hallmark of starvation in mammals.

RELATED: Giant rhino skeleton found in China: one of the largest land mammals in history (Look)

“It’s just amazing what we were able to see and do with this data,” said co-lead author Clement Bataille, a University of Ottawa researcher who led the collaborative modeling effort with Amy Willis at the University of Washington.

Finding out more about the life of extinct species satisfies more than curiosity, said Wooller, a professor at UAF’s Northern Engineering Institute and the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences. Those details could be surprisingly relevant today, as many species adapt their movement patterns and ranges with changing weather.

“The Arctic is undergoing a lot of change now, and we can use the past to see how the future unfolds for species today and in the future,” said Wooller. “Trying to solve this detective story is an example of how our planet and our ecosystems react to environmental change.”

UNEARTH Fascinating stories for your friends by sharing this story …

[ad_2]

source material