[ad_1]

For centuries, the inhabitants of the Baltic nations have used ancient amber for medicinal purposes. Even today, babies are given amber necklaces that they chew on to relieve teething pain, and people put powdered amber into elixirs and salves for its purported anti-inflammatory and anti-infective properties.

Now, scientists have identified compounds that help explain the therapeutic effects of Baltic amber and that could lead to new drugs to fight antibiotic-resistant infections.

Each year in the US, at least 2.8 million people contract antibiotic-resistant infections, leading to 35,000 deaths, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We knew from previous research that there were substances in Baltic amber that could lead to new antibiotics, but they had not been systematically explored,” says Elizabeth Ambrose, Ph.D., who is the principal investigator on the project. “We have now extracted and identified several compounds in Baltic amber that show activity against gram-positive bacteria resistant to antibiotics.”

Ambrose’s interest originally stemmed from his Baltic heritage. While visiting his family in Lithuania, he collected samples of amber and heard stories about its medicinal uses.

The Baltic Sea region contains the world’s largest deposit of the material, which is fossilized resin formed about 44 million years ago.

MORE: An avocado a day can keep gut microbes happy, study shows

The resin oozed from the now extinct pines in the Sciadopityaceae family and acted as a defense against microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi, as well as herbivorous insects that would be trapped in the resin.

Ambrose and graduate student Connor McDermott, who are at the University of Minnesota, analyzed commercially available Baltic amber samples, in addition to some that Ambrose had collected.

“A major challenge was preparing a homogeneous fine powder from the amber stones that could be extracted with solvents,” explains McDermott. He used a tabletop jar rolling mill, in which the jar is filled with ceramic beads and amber stones and turned on its side. Through trial and error, he determined the correct ratio of pearls to pebbles to produce a semi-fine powder. Then, using various combinations of solvents and techniques, he filtered, concentrated, and analyzed the amber powder extracts using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

Dozens of compounds were identified from the GC-MS spectra. The most interesting were abietic acid, dehydroabietic acid and palustric acid, organic compounds of 20 carbons and three rings with known biological activity.

Because these compounds are difficult to purify, the researchers purchased pure samples and sent them to a company that tested their activity against nine bacterial species, some of which are known to be resistant to antibiotics.

“The most important finding is that these compounds are active against gram-positive bacteria, such as certain Staphylococcus aureus strains, but not gram-negative bacteria, ”McDermott says. Gram-positive bacteria have a less complex cell wall than gram-negative bacteria. “This implies that the composition of the bacterial membrane is important for the activity of the compounds,” he says.

RELATED: A single injection reverses blindness in a patient with a rare genetic disorder: another RNA success

McDermott also sourced a Japanese stone pine, the closest living species to the trees that produced the resin that became Baltic amber. He extracted resin from the needles and stem and identified slalarene, a molecule present in the extracts that could theoretically undergo chemical transformations to produce the bioactive compounds that the researchers found in the Baltic amber samples.

“We are excited to move forward with these results,” says Ambrose. “Abietic acids and their derivatives are potentially an untapped source of new drugs, especially for treating infections caused by gram-positive bacteria, which are becoming increasingly resistant to known antibiotics.”

CHECK OUT: Yale Scientists Successfully Repair Injured Spinal Cord Using Patients’ Own Stem Cells

The researchers presented their results at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society, which runs through April. As scientists study the active properties of other traditional medicines from around the world, it will be exciting to see what other findings emerge.

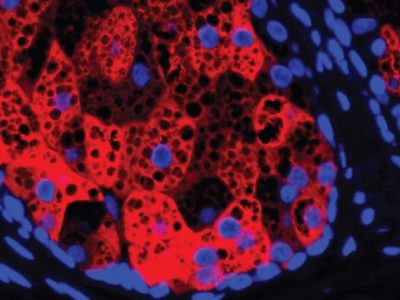

Source: American Chemical Society; Featured Image: Connor McDermott

HELP your friends’ news shine with good news – share this story …

[ad_2]

Original source